BRICS Plus: New World Order after the Pax Americana?

08 April 2024

The political and economic interests of the heterogeneous group of countries are too diverse to seriously jeopardise Western supremacy. However, as a bloc, they would be in a position to pressure the West because of their huge energy reserves

image credit: istock.com/Dilok Klaisataporn

Not everyone is happy with the current balance of power in the world. The BRICS states of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa want to change the geopolitical and geoeconomic order and form a collective counterweight to the United States and the West. At the beginning of 2024, the alliance was expanded by five countries and is now called BRICS Plus, although Argentina rejected its invitation at the last minute at the instigation of its new president, Javier Milei.

At this point, let’s have a brief digression on the history of its creation. The post-Cold War era has been dominated by the so-called Pax Americana, which – until recently – has provided a relatively stable order in which the US and its allies have largely set the geopolitical and geoeconomic tone. The vast majority of world trade is conducted in US dollars, and in international bodies and organisations such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank the US is the dominant heavyweight alongside the other G7 states. In 2009, Brazil, Russia, India and China founded the BRIC group of states in the hopes of changing this. When South Africa joined in 2010, BRIC became BRICS. At the beginning of 2024, Saudi Arabia, Iran, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt and Ethiopia joined on the initiative of Beijing, turning BRICS into BRICS Plus. Chinese President Xi Jinping particularly hopes that this will open up new opportunities in his efforts to end America’s global dominance.

End of American dominance and protection against sanctions

While three of the new BRICS Plus members – Saudi Arabia, Iran and the UAE – are important oil and gas producers, Egypt and Ethiopia are key players in Africa with large populations. With its economy suffering massively under US economic sanctions, Iran is urgently looking for new trading partners. All these middling powers have a common interest, which the well-known political scientist Ivan Krastev formulated as follows: they want to be at the table and not on the menu. In other words, they want to trade as little as possible via the US-dominated international financial system, they want to be less dependent on the West and, above all, they want to take the bite out of any Western economic sanctions. These aims are precisely why bringing some major fossil fuel producers into the bloc has a particular appeal to China, the leading BRICS power. Beijing could be preparing for war against Taiwan – at least as an option. In the various war scenarios that China’s leadership is probably playing through, possible sanctions by the West are likely to play a prominent role, especially given the harsh punitive measures taken against Russia following its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Having Saudi Arabia, Iran and the UAE on its side in the event of a conflict would be economically vital for the supply of oil and natural gas as well as politically helpful.

Heterogeneous alliance

But how realistic is the prospect of establishing a new world order and dislodging the US dollar as the global reserve currency? Apart from their scepticism towards the US-dominated international economic and financial system, the BRICS Plus members do not share much in common. On the contrary, India and China have been engaged in a bloody border conflict in the Himalayas for decades. New Delhi has clearly taken Washington’s side in the geopolitical struggle between the US and China while also being politically and militarily supported by the latter. Moreover, while India’s economy is still relatively closed and primarily focused on the domestic market, China’s is closely intertwined with those of the US and the EU, even if there are tendencies towards decoupling. On the other hand, Saudi Arabia and Iran are arch-enemies who only resumed diplomatic relations in May 2023 under Chinese mediation and remain hostile to each other in the Middle East. While Saudi Arabia maintains a strategic security and energy partnership with the US, Iran is repeatedly on the brink of war with Washington and its ally Israel.

Apart from wanting to play a bigger role on the global stage, the five founding members of BRICS have never really been like-minded. While Russia and China have increasingly positioned themselves as antipoles to the US, India has gradually drawn closer to the US to counter a more aggressive China. Although they occasionally toy with the anti-American option, South Africa and Brazil continue to foster close ties with the US in both economic and political terms. It is no coincidence that India, Brazil and South Africa are democracies, while Russia and China are autocracies – and ones that get along very well with the authoritarian rulers of Iran and Saudi Arabia.

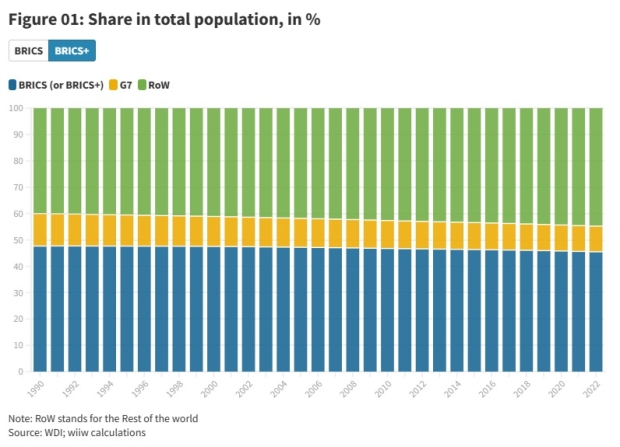

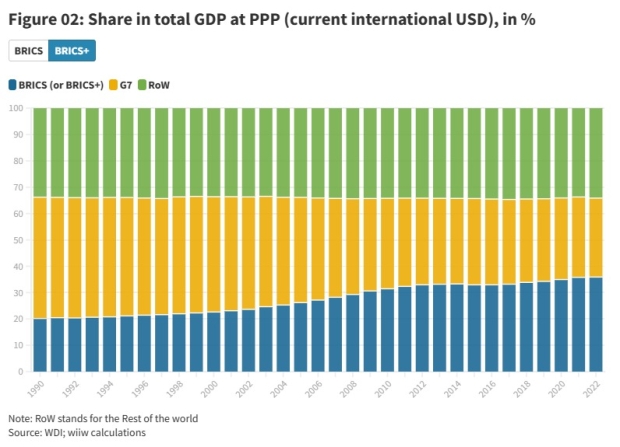

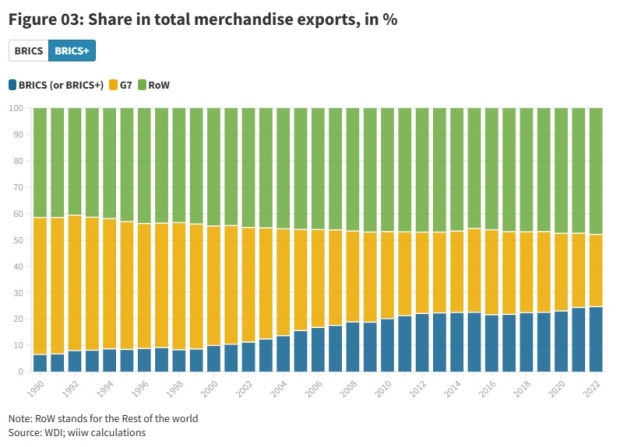

In addition to having diverging political and economic interests, the BRICS Plus countries also differ strongly in terms of their respective economic and demographic weight.Collectively, the five BRICS countries account for around 41 per cent of the world’s population, approximately 32 per cent of global economic output (adjusted for purchasing power), and roughly 20 per cent of all goods exported worldwide. If we add the five countries that make up the “Plus” part, the combined bloc only accounts for slightly more – around 45 per cent of the world’s population, 36 per cent of global GDP, and 25 per cent of global goods exports.

Figure 1 - BRICS+ countries' share of the world's population, in %

Figure 2 - BRICS+ countries' share of global GDP in purchasing power parities, in %

Figure 3 - BRICS+ countries' share of global merchandise exports, in %

Thus, the expansion is likely to fundamentally alter the character of the previously exclusive club of leading regional economies. It will be replaced by a curious mixture of very large, large, medium-sized and small countries, some of which are pursuing very different interests. What’s more, the BRICS Plus group is already clearly dominated by China, which accounts for almost two-thirds of the bloc’s economic output and 39 per cent of its population. As understandable as Beijing’s claim to leadership may be against this backdrop, these imbalances are problematic for ensuring joint action on an equal footing. The balance between the interests of the junior partners and dominant China is therefore likely to remain delicate. And it is unlikely that forming an internationally relevant bloc capable of cohesive action out of such a heterogeneous group of countries will represent a genuine success for Beijing.

BRICS Plus as a potential raw-materials superpower

As the figure above shows, even if their political interests were more aligned, the combined economic weight of the BRICS Plus countries would not be enough – at least in the short to medium term – to turn the US-dominated world order on its head. However, there is one exception, as the BRICS Plus countries would collectively be in a dominant position when it comes to raw material deposits. With the inclusion of Saudi Arabia, Iran and the UAE, the bloc would account for 43 per cent of global oil production and a very large share of global oil reserves. Almost 40 per cent of the rare earth deposits required to manufacture batteries for electric vehicles, power storage systems and microelectronics are in the hands of China, which also has a near monopoly on their processing. Thus, when it comes to the supply of raw materials, the BRICS Plus bloc could potentially put the West under considerable pressure – in a scenario with echoes of the OPEC oil embargo of 1973.

G7 and US dollar still dominant

From an overall economic perspective, however, a reorganisation of the world and an end to the US dollar as the reserve currency is a pipe dream of Beijing, Moscow and Tehran, which will not come true in the foreseeable future. As the most important industrialised countries of the West, the G7 nations still jointly account for around 30 per cent of global GDP, just under 10 per cent of the world’s population, and roughly 27 per cent of all exported goods. As still the largest economy and the only military superpower, the US continues to dominate not only the G7 but also the world. Around 62 per cent of global currency reserves are invested in US dollars, compared to just 2 per cent in Chinese yuan. The BRICS group’s track record to date also speaks against a rapid end to the Pax Americana. The bloc’s greatest success so far has been founding the New Development Bank in 2014, which is modelled on the World Bank. To date, the bank has issued loans with a total value of just over 30 billion US dollars. Tellingly, most of the loans have been granted in US dollars.

From China’s point of view, however, the meagre balance sheet of the previous BRICS format and the uncertain prospects for BRICS Plus are acceptable. The old BRICS format did not really advance the interests of the rulers in Beijing. So, their thinking goes, why not try a new start that could at least irritate the US and its partners while possibly strengthening some bilateral relations, especially in the Middle East, where China is keen to gain more influence? At the same time, the BRICS Plus initiative allows some smaller powers to position themselves as players in the geopolitical competition of the incipient Cold War 2.0 between China and the US so that they can avoid becoming mere pawns or a theatre of war in this conflict.